Hot as a Pistol | by Kevin

Before we know it, spring practice will be over, beginning the Long Summer's Wait. Although now is too early to predict the Irish starting twenty-two, let alone guess the depth charts of every opponent, it's never too early to do a little advance scouting. There's no time like the present to meet our first opponent in 2009, the University of Nevada-Reno, and their innovative "Pistol" Offense.

Before we know it, spring practice will be over, beginning the Long Summer's Wait. Although now is too early to predict the Irish starting twenty-two, let alone guess the depth charts of every opponent, it's never too early to do a little advance scouting. There's no time like the present to meet our first opponent in 2009, the University of Nevada-Reno, and their innovative "Pistol" Offense.

Nevada is the classic no-upside opponent: good team, little cachet. They're an offense-driven squad (though their run defense has become more stout, they did yield 34 points a game to Division IA opponents last year). Nevada's 508 yards of offense and 37.6 points per game ranked 5th and 12th in the nation, respectively. Nevada moves the ball well both on land (277 yards rushing per game) and through the air (230 yards passing per game). How do they do it?

Pistol Overview. Head coach Chris Ault developed the Pistol offense in 2004 as a way to keep up with the high-octane output of Nevada's pass-heavy WAC peers, while retaining the balance of an effective running game. In the base Pistol, the quarterback lines up in the shotgun, with -- this is the wrinkle -- the tailback directly behind him.

Pistol Overview. Head coach Chris Ault developed the Pistol offense in 2004 as a way to keep up with the high-octane output of Nevada's pass-heavy WAC peers, while retaining the balance of an effective running game. In the base Pistol, the quarterback lines up in the shotgun, with -- this is the wrinkle -- the tailback directly behind him.

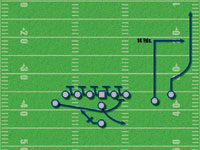

| A typical shotgun formation looks like this. | On the other hand, here's the basic Pistol alignment. |

|  |

Note the quarterback still in shotgun, but with the running back behind him.

The shotgun formation always improves the quarterback's ability to see and read the defense, and shotgun formations with a halfback allow for quick handoffs and play fakes. The Pistol setup adds one more offensive advantage: the quarterback obscures the view of the running back. Defenses look to the interior linemen and running back to figure out what's going on and how to attack, so the single-file Pistol formation can disorienting to linebackers and the rest of the defense.

Here's a glimpse of the Pistol in one of its most prolific outings: a 69-67 loss to Boise State in 2007.

Other teams have used the Pistol formation for selected plays; Florida used it in short yardage against Alabama in the 2008 SEC championship game. But no team in football uses it as heavily as Nevada.

How does it work? Most Nevada plays start the same way: the quarterback (third-year starter Colin Kaepernick) takes the snap, does a half-pivot, and either: a) hands off to the halfback; b) fakes the handoff (either a full sell, or just a quick pivot) and runs; or c) fakes the handoff and passes. Like the spread option, the guessing game can cause havoc with defensive timing.

Nevada's run-game bread and butter are zone runs, primarily an inside zone "slice" play and the outside zone, or stretch. They run the stretch to both the weak and strong sides, and typically run the slice -- aided by the strongside receiver, who "slices" in behind the weakside guard and tackle to pick up a linebacker or safety. Both are designed to play to the strengths (and/or minimize the weaknesses) of smaller, quicker offensive linemen, although Nevada's line is not tiny: their guards and tackles are lighter than ND's, but not significantly so.

They run well: Vai Taua, who will return this fall, had 236 carries (17th in the country). His 1,521 yards (at a startling 6.4 yards per carry) made him the nation's 8th leading rusher. He added 15 touchdowns on the ground, which were good for 17th in the country -- and second on his own team. Kaepernick had 17 touchdowns of his own, and 1,130 yards on the ground (add quarterback draws and dives to that bread-and-butter lineup). Pending an appeal to the NCAA for a sixth year of eligibility, Luke Lippincott may provide a potent additional weapon; Lippincott was the WAC rushing leader in 2007.

Though the inside zone and QB keepers may call to mind the Florida and other spread option attacks, Nevada's passing game is a bit more vertical. Those pass plays generally spring from play-action fakes off the slice and stretch. Kaepernick attempted 383 passes in 2008, 33rd most in the country, for 2849 yards in the air. His meager 54.3% pass completion rate rendered the passing attack less efficient than the Wolfpack ground game, though Kaepernick still averaged a respectable 7.44 yards per attempt.

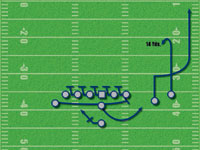

To get a feel for the Pistol in action, American Football Monthly (an indispensable resource for articles like this) examined in detail a favorite Nevada pass play, the Zone Pass Boot. The Zone Pass Boot starts as a run fake -- the line sets up to block as they would the slice, and the strong side receiver (the receiver on the right side above, but left side in the diagram below), slices across the formation to block between the weak side guard and tackle. All of this tracks what would happen on the inside zone. But in the Zone Pass Boot, the quarterback rolls into naked bootleg (without a lead blocker) to the strong side, carries that out a step or two, and find either his slot receiver or wideout. As the following diagrams show, the slot receiver might draw a mismatched linebacker and cut out, or he might run a wheel route, turning upfield, while the wideout runs a curl:

Nothing about these routes is particularly groundbreaking. The existence of a true vertical passing game, however, may give defenses pause in taking a send-the-house approach to stopping the Nevada run attack.

The Nevada playbook obviously goes deeper than three or four plays. Thanks to Michael, this link gives a fuller picture of the various Pistol options, which also include counters, tosses, and a few spread-type pass plays, including the Belly Pass (slide 10), and a shuffle pass Nevada may turn to if ND sends the house a few too many times.

If Nevada can have any success in their vertical passing game -- shown in both the plays above, as well as slides 11 and 12 from the linked playbook -- they (like most teams with a deep threat and a good run game) can become very tough to stop. Their counter trap and already confusing sight lines, along with their willingness to run the play-action for deep strikes, may keep a defense on its heels and further help the line get into a rhythm on the staple run plays.

Defending the Pistol. I offer no purported solutions to defending the Pistol. Nevada scored 38 points a game last year against Division I opposition. Boise State coach Chris Petersen, who coached 13-win and 12-win teams the last two years, offered no strategy to defend the pistol, and said only, "we're going to have to score some points on offense." But I do have a few on-paper ideas. Four teams -- Nebraska during the 2007 season, New Mexico in the 2007 New Mexico Bowl (at the end of the 2007 season), and Texas Tech and Missouri in 2008 -- have limited Nevada's scoring output. These games might provide some hints on how to stop Nevada's offense (one way: abuse their defense and demoralize the rest of the team) .

New Mexico, which shut out Nevada, had the advantage of playing Nevada in miserable weather (near-freezing temperatures and rain), and at the end of Kaepernick's first year at quarterback. New Mexico limited him to 13 of 31 passing, and only 40 yards rushing. The nice thing about playing a dual-threat quarterback? Take him off his game, and you avoid two threats instead of one. (Some video of the New Mexico game here.)

Nebraska may have had a similar plan, but the Husker offense carried the day, proving that an unstoppable run offense can be a defense's best friend. Nebraska ran for 413 yards and gained a total of 625 yards in a 52-10 rout, and held the ball for an amazing 40:13. Though it didn't likely matter, Kaepernick sat out the game with an injury.

Missouri did not dominate the time-of-possession battle, but they did make life miserable for the Nevada offense by scoring constantly and forcing Kaepernick into an air war. Missouri won 69-17, with 652 total yards and touchdowns or field goals in each of its first ten possessions. Texas Tech won 35-19. Both the Tech and Missouri games revealed a potential Wolfpack soft spot: the red zone. Nevada had 362 total yards, and only one turnover against Missouri, but still only found the end zone twice. Against Tech, they put up 488 yards, but again only scored twice.

Other than bad weather and a never-ending string of touchdowns -- neither of which ND can necessarily count on in early September -- a few additional half-baked thoughts on slowing down the Pistol:

1. Tricky formation or not, the defensive line's job is pretty much the same. Control scrimmage, win game. Further, if Notre Dame continues to show the five-man under front they often used last season, with a fifth defender "under"balanced on the weak side of the line, that end should have a pretty good view of Taua before the snap. That the remaining two middle linebackers are a half-step off at the snap may not matter if the line holds its ground and/or gets into the backfield.

2. ND should benefit from roster attrition. Nevada has lost two of its top receiving threats. Marko Mitchell (61 receptions, 1,141 yards) and Mike McCoy (54 receptions, 620 yards), have graduated. Chris Wellington returns from his 42 reception, 632 yard campaign. Nevada will need to rely on an as-yet undetermined mix of Malcolm Shepherd, Brandon Wimberly (both red-shirted last year), JUCO transfer Maurice Patterson, and newcomer L.J. Washington, as well as returning tight end Virgil Green. The less effective the passing game is, the more ND can focus on containing Kaepernick, Taua, and the rest of the running game.

3. Relative to run plays out of the I, and even compared to shotgun formations in which the halfback starts next to the quarterback, Pistol plays appear to take a little longer to develop. The halfback begins the play seven yards behind the line, and if the quarterback must pivot and hand the ball off, that should take longer to get to and beyond scrimmage. Furthermore, if Kaepernick is still the 54% passer he was last year, and/or his new receivers aren't yet ready to go -- and with Tenuta calling the shots -- we might as well send something like this.

Thanks for indulging a little early-season scouting. If you have any suggestions on other opponent schemes we should explore, shout 'em out.